What 'Star Wars' Gets Wrong about Space Battles

May the Force equals mass times acceleration ...

I’ve loved Star Wars ever since my babysitter brought over the VHS set when I was nine. I read all the old Legends books and still dutifully watch every piece of visual media that comes out, regardless of varying levels of quality. I owned all the reference books in high school, from The Essential Guide to Characters to The Wildlife of Star Wars. A giant Razor Crest LEGO set sits above my desk as I write this. I used to play a game with my brothers in which we each had to name an alien race and a planet for each letter of the alphabet—first one to come up empty loses. (If you ever play, you may want to remember the planets Quermia, Xagobah, and Zeffo. You’re welcome.)

I mention all this not only to establish my nerd cred, but also to make it clear that any criticism of the franchise I’m about to fire off comes from a place of love.

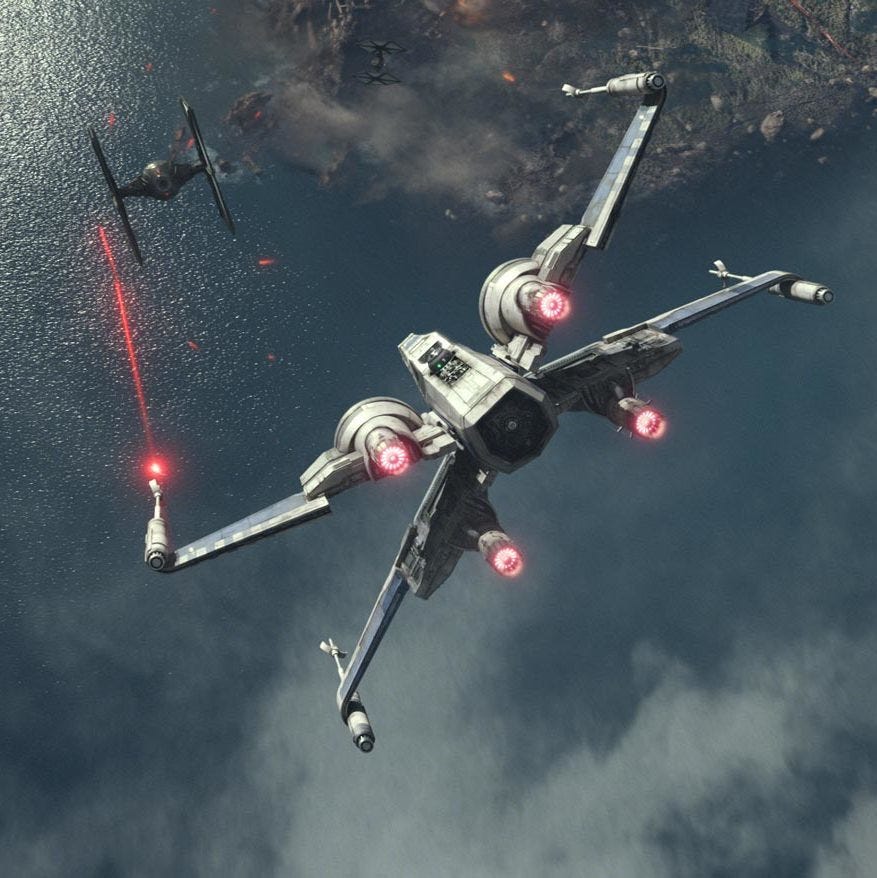

I also adore Star Wars’ space battles—Naboo, Coruscant, Yavin, Endor, Scarif, D’Qar, Fondor, Bilbringi, and all the many others from canon and Legends. Nothing gets my nostalgia going like the sight of dozens of starfighters zipping through the void of space in a dizzying tango of death while capital ships rumble overhead, their turbolasers flashing. Ahhhh … you can never get enough space battles.

Still, the battles in Star Wars aren’t what you might call scientifically accurate. Not even a little bit. There’s no sound in space. Maneuvering doesn’t work like that. How are they even communicating? And that’s just the start. If you think about it too much, your head starts to hurt more than Jango Fett’s after he ran into Mace Windu’s lightsaber.

Luckily, the implausibility of these spectacles has never prevented me from enjoying them. Nor should it prevent anyone else from doing the same. Give me some lasers flashing to triumphant John Williams fanfare over a textbook about the proper behavior of gravity any day. Still, pointing out how Star Wars space combat falls short of actual physics offers a fresh opportunity for writers of military sci-fi and space opera.

So … you wanna write your own scientifically plausible extraterrestrial combat?

Join me, and together we’ll … talk some science.

In Space, No One Can Hear You Go PEW-PEW!

First, a quick disclaimer: I’m no physicist. I didn’t even like my science classes in college. I was a comms major then, and I now work as a creative director at an ad agency while I inch toward the eventual goal of full-time fiction writing. Everything contained in this article came from my own research and extensive consumption of science fiction, and I welcome any notes regarding any errors on my part in the comments.

Still, my relative inexperience in the realm of physics means I’m forced to explain these concepts in terms a layperson like myself can follow, so rest assured that nobody’s heads will explode from exposure to esoteric concepts or dense walls of unintelligible notations.

Okay, got that out of the way? Great. Let’s start with the most obvious way in which Star Wars differs from reality: the presence of sound in space. In real life, there’s no medium to conduct sound waves in the void. (At least nothing with the density to matter.) So the TIE fighter’s signature shriek? In a realistic outer-space setting, you couldn’t hear it. Sure, you might hear it from the inside of the ship, but from the outside it would sound a lot like this:

…

…

…

Exactly.

But we all knew that, right? Cool, let’s move on.

Everything is Looking Up

One thing about Star Wars space battles that I never really realized until I thought about it is that every ship seems to maintain the same orientation. In other words, everybody in the galaxy seems to have mutually agreed to keep their feet pointed in the same direction. X-wings and TIE fighters duke it out on a single horizontal plane, capital ships line up broadside like naval warships, and the audience always knows which way is “up.” You can see it here in the battle of Coruscant in Revenge of the Sith, for instance.

But does it have to be like that?

Gravity gives us a sense of “down” on planets, but once you’re out in the void, directions are arbitrary. A fleet of starships could approach from any angle—flipped, rotated, or even coming “sideways” relative to one another—and it wouldn’t matter. Astronauts on the ISS, for example, often float around upside down without even realizing it, because orientation in orbit is purely relative.1

Interestingly enough, the only time I’ve ever seen Star Wars ships not arranged on the same plane is in the dubiously canon but still beloved animated Clone Wars series from 2003, the precursor to the 2008 canon series we all know and love. Here you can see the Battle of Coruscant again, but this time they’re coming in from every direction.

It makes me think there’s a missed opportunity in all this—one that you might correct in your own space battles. Imagine enemies dropping “from above” or “below” in 3D space, or entire fleets converging from disorienting angles. If someone’s expecting ships to come from straight ahead or the side, you’re going to blow their little minds just before you blow their ships to little bits.

Somebody should call Grand Admiral Thrawn and tell him I’ve got a great idea he can use. Free of charge.

Going the Distance

I mentioned the common sight of capital ships lining up like earthbound naval vessels. But you wouldn’t see that in real space combat, and not just because you’d have a lot more directions to work with.

I’m talking about the issue of distance.

See, spacecraft—especially the big ones—move very fast. Even a small relative velocity (a few meters per second) when two objects are close can lead to catastrophic collisions. Orbital debris in Earth orbit causes satellite operators to constantly plan course corrections to avoid impacts. Scientists track conjunctions (close approaches) and perform collision avoidance maneuvers precisely because even tiny pieces of debris at high speed (kilometers per second) can punch through shielding.2

Thus, if you have two large ships maneuvering near each other at combat speeds (turning, accelerating, firing thrusters), the chances of accidental collisions (or debris from damaged parts) would increase dramatically. Just ask Admiral Piett of the Executor:

And then there’s fuel costs. To maintain tight formations, each ship would need to constantly adjust its position, velocity, and attitude. In real space, even small corrections cost fuel. Over long battles, that adds up. Ships would prefer being farther apart so they don’t waste precious reaction mass (or coaxium, or whatever Star Wars ships run on these days) on tiny thruster burns just to stay in formation. There’s nothing like atmospheric drag to damp movement—once you fire, you keep moving, and braking or adjusting takes fuel.3

Which leads us to …

Isaac Newton’s Film Criticism

I’m not here to complain about The Last Jedi. I actually like the movie a lot. (You can read about my thoughts here if you want.) But I won’t pretend the movie has no flaws, among them the “low-speed” chase that persists for much of the movie. That’s where the Resistance has been driven from their base on D’Qar, and after a devastating retreat, the remaining ships zip away into space, hounded by the First Order. There are a number of quibbles you might have about this sequence. But here’s what bothers me: as ships run out of fuel, they just . . . fall away.

Isaac Newton would have a thing or two to say about that, assuming you could explain to him what movies were first (he’ll surely also want to know why Episode IV came before Episode I). His first law goes like this:

A body remains at rest, or in motion at a constant speed in a straight line, unless it is acted upon by a force.4

So a ship running out of fuel wouldn’t just slow down; it would keep going at its current speed until it ran into something. The Resistance wouldn’t have to worry about fuel at all, at least while they were going in a straight line. (That’s why the Apollo missions didn’t keep their rockets blazing all the way to the Moon; they accelerated to the right speed, cut the engines, and let momentum do the work. (NASA even calls this a “coast phase.”)5

Of course, running out of fuel in deep space is bad for other reasons — you can’t change course, dodge attacks, or decelerate before smacking into a planet — but it doesn’t make you fall behind. Everyone’s still moving at the same velocity unless some external force intervenes.

(Side note here: Newton’s First Law is also why the bombs in The Last Jedi actually make more sense than the film’s detractors realize. People complain that bombs in space wouldn’t actually fall to their targets. What they don’t realize is that, from an in-world perspective, the bombs are already falling before they reach the void of space, thanks to the artificial gravity that exists in all Star Wars ships. Once they clear the bomb bay, momentum carries the projectiles where they need to go.)

So how would a ship decelerate, then? I’m glad you asked. The only way to stop would be to be “acted upon by a force” (and no, not that Force … haha). You’d need a force pushing the opposite way to slow down. I’ll turn to The Expanse as a notable example of more realistic physics at work. In that universe, when ships reach the halfway point of their journeys, they initiate a “braking burn,” firing a set of engines the opposite way in order to gradually cancel out the forward motion.

But let’s say you kept the rear engines going in a forward course, spending fuel like normal. Let’s say you’re not worried about crashing into anything. Would you maintain a constant speed? No. That’s because of Newton’s second law:

At any instant of time, the net force on a body is equal to the body’s acceleration multiplied by its mass or, equivalently, the rate at which the body’s momentum is changing with time.6

Basically, if you’re applying force, you’re accelerating. Fire the engines, and you don’t just keep going—you keep speeding up.

I Know a Few Maneuvers

Speed aside, there’s also the matter of maneuvering. X-wings and TIE fighters swoop, bank, and spin like F-16s in Earth’s atmosphere. On Earth, planes turn by banking—tilting their wings so lift pulls them sideways. In space, though, there’s nothing to push against: no air, no lift, no atmosphere, nada. A real spacecraft would have to fire side thrusters to rotate, then burn its main engines in the new direction. Without constant course corrections, it would just keep spinning forever.

So how does an X-wing turn? I have no idea. As far as I can tell, those thrusters push the ship forward and in no other direction.

The answer, I suspect, is as mysterious as the name of Yoda’s species.

EDIT: Okay, it’s actually not that mysterious. Several astute readers (such as

and ) have poked a hole in my nerd cred by pointing out that Star Wars lore includes an “etheric rudder.” Timothy Zahn coined the term for Heir to the Empire, and it appeared in a few subsequent books like the X-wing series, though it still hasn’t really caught on. Wookieepedia offers some further insight:The etheric rudder was a device for maneuvering starfighters. It allowed them to make sharp turns without the use of attitude thrusters, allowing for precision thrust vectoring and enhanced maneuverability; in the case of 4L4 fusial thrust engines, maneuverability was so increased that pilots likened it to flying a T-16 skyhopper in atmospheric flight.7

So there you go. This is actually a great example of the fictional universe breaking the laws of physics while providing an acceptable in-universe reason for such a violation, thus reducing the suspension of disbelief required. It’s very thoughtful of Star Wars’s creators. I’m going to write a whole post on this idea soon. But for now…

Sorry, Master Yoda, You’re on Mute

You know that scene in The Empire Strikes Back (now and always the best Star Wars movie—sorry, Gen Z) where Darth Vader is chasing the Millennium Falcon through the asteroid field? He’s teleconferencing with a bunch of Star Destroyer captains as one ship gets hit by an asteroid. Simultaneously, that ship’s captain cries out and disappears, his transmission ended. It’s a great little touch. But could it really happen?

What about all those scenes where people stand around a holoprojector and have cross-galactic Zoom calls?

We all know faster-than-light travel is impossible. This, of course, includes the signals needed to transmit the holograms (unless you invoke some sort of exotic physics, like quantum entanglement, but there’s no evidence Star Wars knows about that). So those signals would need a great deal of time to go from, say, the Jedi Council chamber to the bridge of a spaceship in another sector, resulting in lag of years or more. The farther two ships get from each other, the greater the lag. So a more realistic scenario would be more akin to writing letters—one person sends a message, and after a long wait, the recipient gets the signal. They would then take time to compose a reply and send it off. (Not incredibly cinematic, I’ll admit.)

I should mention that Star Wars actually gets around this issue with hyperspace transceivers, devices that use the same hand-wavey space magic that allows ships to travel through hyperspace and bypass the pesky speed-of-light limit. This is another great example where Star Wars came up with an in-universe excuse for breaking physics, and it works.

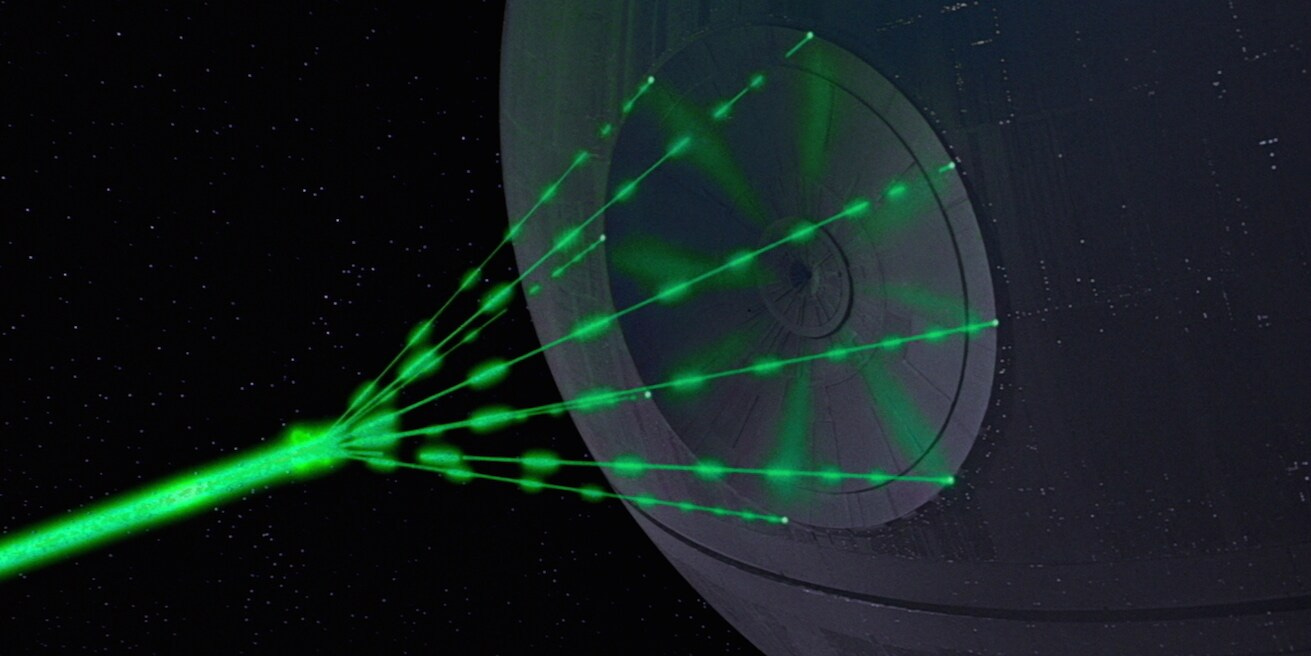

Frickin’ Laser Beams

You thought we were done?

Let’s talk about those streaking blaster bolts and superlaser beams. On screen, they look like bright colored beams arcing through space, but if you apply a little real physics, you’ll realize a laser beam in a vacuum wouldn’t look like much at all. Laser beams are, essentially, photons traveling in (nearly) straight lines. For you to see the beam path (not just the dot where it hits), something has to scatter that light toward your eye. In an atmosphere, dust or fog or water droplets will scatter the beam and make it visible to the side. In the vacuum of space? There’s nothing much to scatter off of. So the beam itself would be nearly invisible until it strikes something and you see the impact.8

In short: in space, you’d see a flash or glint where the beam hits a target, maybe a flare of energy, but you likely wouldn’t see the long glowing streaking line we’re so used to … until it’s too late. And maybe there’s a storytelling idea right there.

If you want to get technical, most “blaster bolts” in Star Wars aren’t really lasers—they behave more like plasma or particle bolts, which could glow as ionized gas interacts with the environment. But since Star Wars calls them “lasers,” we’ll go with that.

The Big Why

These are some pretty glaring errors, right? Forget the whiniest fans’ annual calls to fire Lucasfilm president Kathleen Kennedy—whoever was in charge of physics quality control at Lucasfilm should be terminated immediately. Except … well, obviously, there’s a reason Star Wars fudges the science and gets away with it.

It all comes down to two things. The first? Giving the viewer visual context to help us understand what’s going on. Rhett Alain of Wired suggests that the filmmakers add sound in space because few of us have been to space, so the emptiness just feels wrong—so including the rumbling of the engines reminds us of a big ocean vessel passing by, giving us a point of reference.9 It’s the same with ships sticking to a single visual plane: George Lucas (and just about every space opera director since) borrows staging tricks from naval battles, as Star Destroyers and Mon Calamari cruisers line up as if they’re trading broadsides at sea. It’s not realistic, but it gives us visual order in what would otherwise be chaos.

The other reason, naturally, is that these changes to real physics are in the service of what we in the business call The Rule of Cool: visible lasers are way cooler than invisible ones. And while a silent space battle done right can be haunting (see The Expanse again, especially in the early seasons), sound design adds a welcome layer of visceral thrill. Maybe the sounds were added for the benefit of the viewer by whoever’s telling the story in-universe. (Like the Whills—there’s a deep cut for you.)

As I said from the start, nobody gives a flying gundark’s tail that Star Wars takes the laws of physics and throws them in the trash compactor. The franchise puts a spectacle on screen that’s crafted for maximum coolness, Isaac Newton be damned. And it works. If you want to write a more scientifically accurate version, knock yourself out! Feel free to pick and choose the laws you want to follow.

At the end of the day, nobody fell in love with Star Wars because Neil DeGrasse Tyson gave its physics two thumbs-up. We fell in love with it because it felt real — because when an X-wing screams through the void and that Williams music swells, something in our lizard brains goes, Yes! That’s right! That’s what flying through space should feel like.

That’s the point. Star Wars doesn’t care about Newton or NASA; it cares about myth, momentum, and emotion. The science doesn’t always make sense, but the storytelling physics does.

Did you enjoy this post? If so, consider checking out my fantasy serial The Archangel’s Gift, about a world of floating islands beset by demons. It’s got nothing to do with Star Wars on the surface, but like most of my fiction, it owes a lot to the elements I first loved about Star Wars: epic battles, memorable characters, and fantastic worlds worth exploring.

https://www.nasa.gov/learning-resources/for-kids-and-students/what-is-microgravity-grades-5-8

https://science.nasa.gov/blogs/imap/2025/09/24/coast-phase-begins-2/

https://starwars.fandom.com/wiki/Etheric_rudder

https://physics.stackexchange.com/questions/20259/what-makes-some-laser-beams-visible-and-other-laser-beams-invisible

https://www.wired.com/story/the-phony-physics-of-star-wars-are-a-blast/

In some ways, the worst one was Wrath of Kahn, because the Star Trek characters are all snooty about how poor old Khan hasn't been in space all his life, still has 2-D thinking, unlike the space-trained Federation spacemen.

So then they act like a submarine: sink "down" into the nebula, hide "underwater" as it were, then "Surface" back up to Khan's plane, behind him, and shoot him in the ass.

Except there's no need to "surface" back up 10,000metres to shoot Khan at all. They could just rotate the Enterprise 90 degrees in pitch, and shoot Khan in the tummy as he "passes overhead".

It's not just that this is understood by space-trained astronauts: it's understood by mid-20th-century pilots who invented the "dogfight", so named because dogs roll over and over each other as they attack from all angles. Chuck Yeager could have flown the Enterprise to a quicker win. Pilots love nothing better than attacking from above, though, with gravity advantage, and best of all, come out of the Sun at them. I learned that watching "Battle of Britain" when I was six, in 1965.

I recall that the remake of Battlestar Galactica had (almost) no sound in the space battles and despite being for the small screen still felt very cinematic.